Video games have permeated just about every corner of modern society. What was once a niche hobby built by small teams tinkering in basements and offices has become a massive, global industry—one where billions of dollars change hands constantly between consumers, publishers, shareholders, developers, marketers, and governments. The scale at which this entertainment product moves, and the power these corporations wield, is genuinely staggering.

The forefathers of video games could not have imagined what their brainchild would evolve into: a sprawling, multimedia, corporate ecosystem involving thousands of people meticulously adjusting the curvature of Tracer’s ass. With the size and scope of the modern industry, a reasonable question emerges—is ethical consumption of video games even possible? And if it is, how far would someone need to go to actually achieve it?

Culling the Herd

The first major hurdle to ethical consumption is the human capital employed by these companies. The biggest players in gaming rarely exist in isolation. They’re arms of even larger entertainment and technology conglomerates. Microsoft operates through Windows, Azure, and enterprise software while also controlling a massive gaming portfolio. Sony balances its gaming arm alongside movies, television, and music.

Between the two, Microsoft employs roughly 20,000 people in its gaming division, while Sony employs around 12,000. Ironically, that scale ties directly into the ethical conversation—both companies have conducted massive layoffs in recent years. Worker rights, job stability, and long-term sustainability are already on shaky ground before we even boot up a console.

If we remove those two giants from the conversation, we quickly fall into murkier waters. Tencent has become synonymous with questionable business practices, particularly in recent years, making it a non-starter for many ethical consumers. NetEase initially flew under my radar, but a little digging revealed a surprisingly familiar footprint: Marvel Rivals, Chinese versions of Blizzard games, Destiny: Rising, Harry Potter: Magic Awakened, Lord of the Rings: Rise to War, and Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night.

Chinese companies are so tightly intertwined with the Chinese government that their presence always gives me pause. Whether that concern is justified or overblown depends on your tolerance for state influence, but it’s an unavoidable part of the ethical calculus.

Then there’s Sea Ltd., which accepted massive investment tied to Chinese capital. Roblox has faced serious allegations regarding child safety and moderation failures. Electronic Arts and Take-Two Interactive round out the upper tier with their own laundry lists of ethical issues—Saudi investment money, aggressive monetization, mass layoffs, labor disputes, and a habit of buying studios only to hollow them out or shutter them entirely.

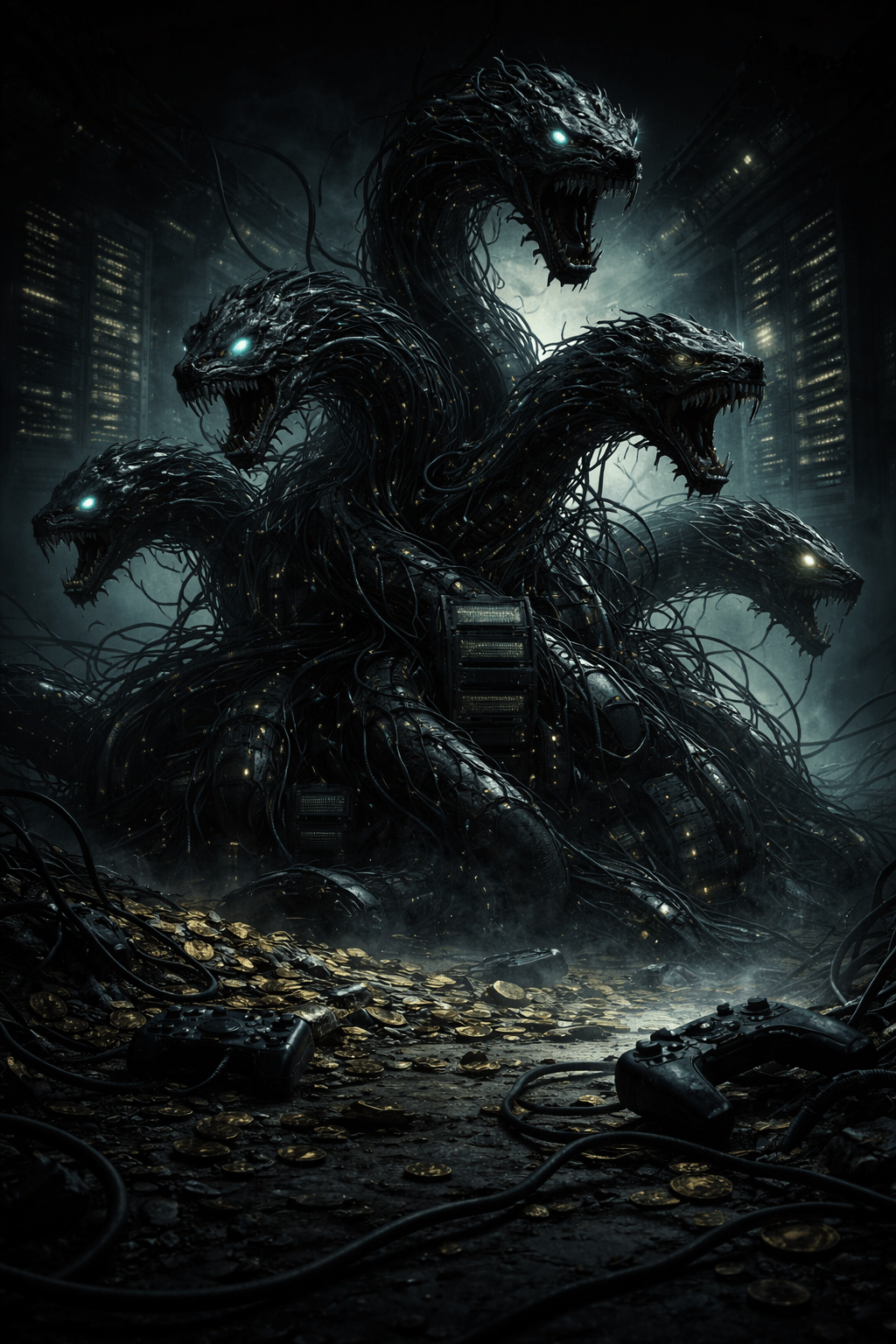

Out of the top seven or so companies dominating the industry, the only one that consistently lands closer to the “less evil” end of the spectrum is Nintendo. That’s not because Nintendo is benevolent, but because it’s old. The company’s long history and aversion to buybacks and shareholder appeasement have resulted in a war chest so large it borders on comical. Nintendo hoards cash like Smaug guarding a mountain of gold—trillions of yen, enough to survive downturns without immediately sacrificing its workforce on the altar of quarterly growth.

The World Is Owned by Four Companies

Once you start dealing with the kind of money the modern games industry generates, mergers and acquisitions become inevitable. Nearly every major acquisition worth over a billion dollars has occurred since 2005, which says a lot about both the industry’s explosive growth and how rapidly it consolidated.

Microsoft stands out as the industry’s apex predator, with three of the largest acquisitions in modern gaming history: Activision-Blizzard in 2023, ZeniMax Media in 2021, and Mojang in 2014. The Saudi government—our favorite recurring character—has also planted flags throughout the industry, holding stakes in EA, Niantic, and esports organizations like ESL and FACEIT.

The incestuous nature of these relationships becomes increasingly absurd the deeper you dig. Activision merged with Vivendi Games in 2008, purchased King in 2016, and was then absorbed by Microsoft in 2023. Take-Two bought Zynga in 2022, which had previously acquired Peak in 2020. EA, buoyed by Saudi capital, snapped up Glu Mobile, Playdemic, Codemasters, BioWare, Pandemic Studios, PopCap, Jamdat Mobile, Playfish, and Respawn over the years.

Then there’s the video game Grim Reaper: Embracer Group.

Embracer spent the late 2010s and early 2020s on a buying spree that defied reason. Starting with Saber Interactive in 2020, the company went on to acquire Gearbox, Easybrain, Aspyr, Crystal Dynamics, Eidos-Montréal, and Square Enix Montréal, among many others. Mapping Embracer’s corporate structure requires a corkboard, red string, and a mild drinking problem.

Then reality arrived. A major investment collapsed, stock prices tanked, and by mid-2023 the layoffs began. Projects were canceled, studios closed, others sold off for parts. The cycle continued into 2024 and beyond. Embracer became a case study in corporate hubris and the dangerous belief that infinite growth is both possible and desirable.

It’s Crunch Time, Baby

Crunch—the practice of forcing developers to work extreme hours over long periods—remains one of the industry’s most persistent ethical failures. I’m not naïve enough to think overtime can be completely avoided in a deadline-driven creative field. But crunch isn’t accidental. Deadlines are known months or years in advance. When crunch becomes routine, it’s a management failure, not a necessity.

Some of the most famous examples include Cyberpunk 2077 from CD Projekt Red, Red Dead Redemption 2 from Rockstar Games, Sonic the Hedgehog 2 from Sega, Fortnite from Epic Games, and The Last of Us Part II from Naughty Dog.

Crunch can produce incredible results—or spectacular disasters. The problem is that the cost is always human time and health. Most players will never know which games were built on 80-hour weeks and which weren’t. That ignorance makes it easier to tolerate.

Indie games aren’t exempt either. Stardew Valley was famously built through brutal solo crunch. From a purely economic perspective, I’d love to see hard data comparing employee retention rates to review scores and sales figures. Burning out a workforce only makes sense from a business perspective if the result is both critically and commercially successful—and even then, the human cost remains.

GenAI in Games: Skynet or the Chess Computer from The Thing?

In recent memory, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 received notable blowback for its use of generative AI during development. According to the studio, GenAI tools were used strictly for placeholder assets—temporary stand-ins that were later replaced with work created by human artists. That distinction mattered to the developers. It mattered far less to players.

The reaction was swift. For many, the presence of AI anywhere in the development pipeline was enough to taint the final product, regardless of the quality of the game itself. What followed was a familiar internet ritual: moral line-drawing, accusations of laziness or betrayal, and an exhausting amount of bad-faith discourse about what “counts” as real art.

I don’t believe generative AI is inherently evil. More importantly, I don’t believe pretending it doesn’t exist is a viable strategy. The technology is already here, already embedded in creative workflows across multiple industries, and already being used in games whether players are aware of it or not. For better or worse, the conversation isn’t about if AI will be used—it’s about how.

From a purely practical standpoint, it’s difficult to ignore the industry context in which GenAI is being introduced. Video game development is riddled with crunch. Long hours, unstable employment, and relentless deadlines are treated as the cost of doing business. In that environment, automation isn’t just a shiny new toy—it’s a potential pressure valve. If AI tools can handle tedious or repetitive tasks, the argument goes, developers might be spared some of the worst excesses of crunch culture.

That’s the optimistic framing. The problem is trust.

The same publishers now pitching AI as a quality-of-life improvement for developers have a long track record of using efficiency gains to reduce headcount, not workloads. When productivity increases, the benefits rarely flow downward. They flow upward, to shareholders and executives, while workers are asked to do more with less—or are simply shown the door. In that light, skepticism toward GenAI isn’t anti-technology so much as it is historically informed.

There are also broader concerns that can’t be waved away. Generative models are trained on enormous datasets that often scrape creative work without consent. Data centers consume staggering amounts of energy and water. And the more AI systems are allowed to stand in for creative labor, the easier it becomes to justify sidelining the people who built the industry in the first place.

Still, outright rejection isn’t particularly useful either. If a game contains any trace of GenAI—be it placeholder art, automated testing, or procedural generation—the list of “acceptable” games shrinks rapidly. At some point, ethical purity collides with reality.

So where’s the line? As with so many issues in this industry, it’s blurry and deeply personal. Some players draw it at final assets. Others draw it at training data. Others don’t draw it at all. What matters less is where the line exists, and more that it’s being actively questioned.

And if that line feels uncomfortably familiar—if it echoes past promises about inevitable progress and misunderstood technology—that’s because we’ve been here before.

Real-Life Shinra Corp

In writing this piece, I knew I was forgetting something. That familiar gut feeling—the sense that a major ethical flashpoint in the video game industry had slipped through the cracks. I pushed it down, kept writing, and then it hit me later like a delayed status effect.

Non-fungible tokens. NFTs. Remember those?

What we now look back on with a mix of humor and disdain was, for a brief and deeply embarrassing period, treated as the inevitable future of culture itself. Ownership—already a shaky concept in the digital age—was stripped bare. Tech evangelists loudly proclaimed ownership over media that could be duplicated in seconds with a screenshot tool. It was stupid, yes, but it was also revealing.

For a moment, the industry showed its hand.

There was a stretch where Square Enix published letters to shareholders outlining a future divided between players who “play to have fun” and players who would “play to contribute.” Contribute to what, exactly, was never convincingly articulated—some vague blockchain ecosystem where time spent playing games would fuel speculative digital assets. I read it like a spell book. Partially because I’m old, and partially because blockchain discourse is deliberately opaque.

What was clear, however, was the intent.

Games—something inherently joyful, personal, and escapist—were being reframed as extraction engines. Your time, your attention, your enjoyment were no longer the end goal. They were inputs. NFTs weren’t about art or preservation; they were about financializing play itself.

The backlash was immediate and overwhelming. Players, developers, and critics rejected the idea almost unanimously. The message was simple: don’t turn our hobbies into speculative labor markets.

Rather than reflecting on why the idea failed so spectacularly, Square Enix pivoted. NFTs quietly faded from messaging, replaced by renewed enthusiasm for generative AI—another technology pitched as inevitable, transformative, and misunderstood. The reaction was strikingly similar. Loud pushback. Ethical concerns dismissed as fear or ignorance. Progress framed as something players would simply have to accept.

NFTs didn’t just fail because they were impractical or annoying. They failed because they made exploitation visible. They exposed how easily corporations were willing to monetize trust, enthusiasm, and community in the name of growth. In that sense, NFTs weren’t an anomaly—they were a preview.

Most Gamblers Quit Right Before Hitting It Big

Once the industry had tested the waters of turning play itself into a speculative asset, the pivot was almost effortless. Microtransactions didn’t arrive as a radical shift—they arrived as a quieter, more successful version of the same idea. No blockchains, no jargon, no promises of ownership. Just small, constant asks layered gently on top of the experience.

Today, microtransactions are so normalized that they barely register as a design choice at all. Loot boxes, once the most visible and controversial form of gambling-adjacent monetization, are slowly being pushed out by regulation and consumer fatigue. In their place sit battle passes, cosmetic shops, and limited-time offers—systems engineered to feel optional while exerting constant pressure to participate.

While most purchases are technically cosmetic, the psychology is doing heavy lifting. Fear of missing out, social signaling, and status within online spaces are powerful motivators. The monetization isn’t aggressive because it doesn’t need to be. It’s persistent. It’s ambient. It lives in the corner of the screen, waiting.

And once that logic is accepted—that play can be gently nudged, shaped, and optimized for spending—the ethical conversation becomes less about whether monetization belongs in games at all, and more about how far it can be pushed before anyone notices.

Short Story Made Long

So—can you ethically consume video games?

Probably not, at least not perfectly. You can lean indie and dodge corporate consolidation, but then you face GenAI slop and solo crunch. You can buy AAA games, but risk funding labor abuse, government influence, or predatory monetization.

The real question isn’t “Is there an ethical game?” It’s “How much unethical behavior can I tolerate?” There’s no moral high ground here—only varying depths of low ground. Until a genuinely ethical model emerges, we all make compromises, draw lines where we can, and try to enjoy games in the brief time we have on this cursed rock hurtling through space.

Leave a comment